Separate Worlds: My Encounter with the French Education System

Study abroad is about exploring. It’s about discovering new places, trying new food, celebrating different holidays, absorbing the nuances of another languages, and immersing yourself in the daily culture of another country. Leaving your comfort zone is scary, but it is the only way to grow, and, in the end, it can be pretty fun. Amid the whirlwind that is cultural immersion, it is forget about the first part of “study abroad”: studying. For students in CIEE, the semester abroad is still an academic semester with classes, credits, and final grades. That said, the academic semester in France is very different from the average college experience in the U.S. From the first day of class in Rennes, it became clear to me that the French and American education systems are very different.

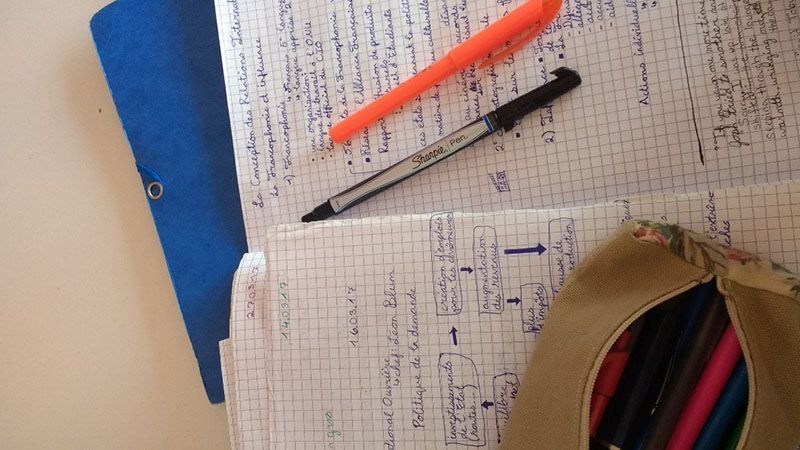

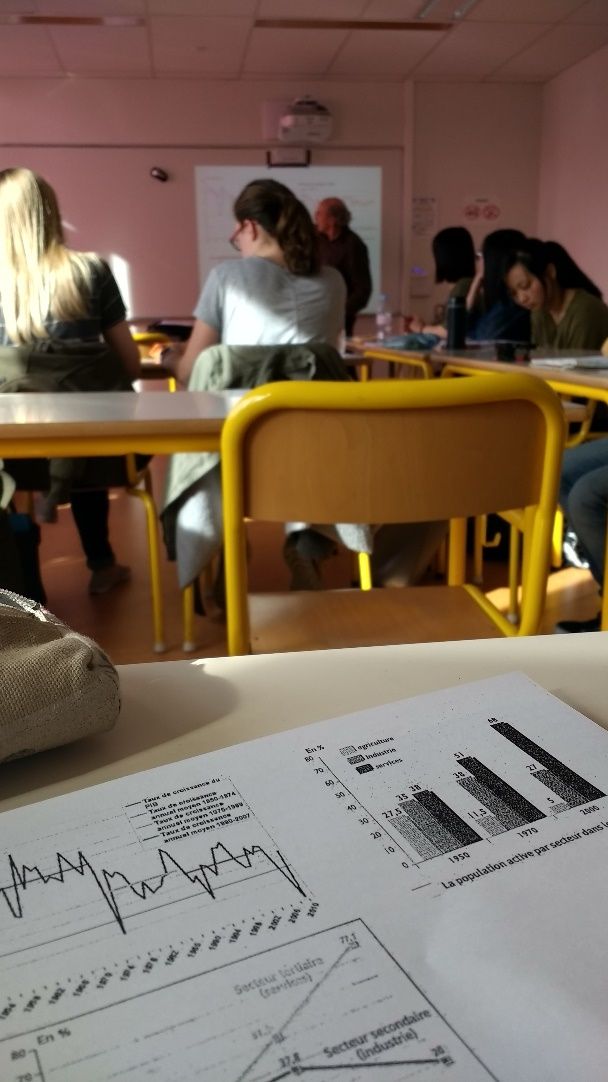

The first difference I noticed was the homework, or rather, the lack of it. In France, teachers tend to give out very few assignments, basing final grades off the results of one or two big tests. Instead, students are expected to take time outside of class to review lessons and study material on their own. The little homework professors do assign is rarely obligatory, but more of a “take-it-or-leave-it” suggestion of how to prepare for the test. I appreciate this approach because it makes students responsible for their education and teaches them how to learn on their own.

Because I was homeschooled, I learned self-motivation and time-management skills from an early age, but I’ve noticed that this is something my friends at college struggle with. American students are taught to rely on weekly assignments, study guides, deadlines, and detailed instructions. In France, without the structure of weekly homework, it is easy to slack off but disastrous for your grade if you do. As a result, my time at l’Université Rennes 2 has been a test in taking initiative and motivating myself to do my best in my classes.

Another striking difference in American and French education is the student-teacher relationship. Many American students on study abroad come from small private colleges where close student-professor relationships are promoted in admissions spiels and praised as one of the most valuable aspects of higher education. It truly is valuable to have professors who are easy to reach during office hours and eager to meet with students outside of class. Professors can become mentors and sources of support and guidance. I had one professor ask the women in his class if someone could babysit his grandchildren, one who gave me her personal telephone number, and another who showed us an adorable video of his toddlers.

This kind of casual, personal environment is unheard of in France. The relationship between student and teacher is more distant, starting with the fact that students must vousvoyer their teachers but the teachers can tutoyer them back. Professors are fully engaged in class and willing to repeat and explain concepts until everyone understands. Outside of class-time, however, they are unlikely to go out of their way to meet one-on-one with a student who needs extra help. To American students, this may seem harsh, but it serves as a way for professors to separate their professional and private lives. Within the French classroom, students are more inclined to argue with the professor. The impersonal atmosphere allows debate to flourish: students speak their minds without fear of offending the teacher, with whom they have no personal connection. In the U.S., the more casual rapport between classmates and professors can impede this kind of frank discussion.

As a whole, the French are very negative; this cultural pessimism is evident in the teaching style of university professors. I first encountered this matter-of-fact style when my teacher handed back an assignment and said (in front of the whole class) “You didn’t quite understand the assignment, so I’m going to ask you to redo it.” It wasn’t a big deal, but I was still a bit taken aback by how upfront she was about my mistake. This fairly representative of French professors: they are quick to point out mistakes and will do so without sugar-coating or beating around the bush. They don’t dole out praise for correct answers either; you have to be a truly exceptional student for a professor to congratulate you on your work. This is evident in the fact that French professors are much harder graders than American teachers. Getting an 8-10 (out of 20), while not good, is adequate. Receiving a 10-14 is considered good, a 14-18 excellent, and a 19 or 20 is practically unheard of. I have gotten many 98’s or 100’s on assignments in the U.S., but I can’t imagine getting a 20/20 here in France. Compared to French teachers, American professors seem extraordinarily lenient.

Simply put, the French education system stigmatizes failure and does not value success. American students should be prepared for what may seem like a harsh atmosphere. Professors will roll their eyes at students who aren’t paying attention or having troubles with a concept; I have even heard a professor call a student “nul” (and they were only sort of joking). It was intimidating and difficult to adjust to, but the French teaching style has grown on me. I now find professors’ blunt honesty refreshing and efficient—instead of coddling students, professors explain precisely what is missing or incorrect so that students can learn from their mistakes.

I’ve only scratched the surface of the differences I’ve reflected on between the French and American university experience. In the end, both have their strengths and weaknesses; there are things the French could teach Americans, and things that the French could learn from Americans. In the end, this just goes to show how important study abroad is. Cross-cultural exposure expands perspectives, strengthens adaption skills, and helps to create strong, intelligent global citizens.

Julia Fulton, Hope College

Related Posts

At Home In France

When I came to Rennes for my study abroad, I thought my biggest lessons would come from my university classes—grammar, vocabulary, literature, all that. But honestly, some of the most... keep reading

Volunteering in Rennes

“You better hurry up, or we are going to get a timer.” A word to the wise: if you are wanting to volunteer at a retirement home in France, make... keep reading

Rugby in Rennes: Playing a Sport Abroad

As I was considering applying for my study abroad program in Rennes, one of my biggest concerns was whether I would fall behind in my sport while I was away... keep reading