Getting COVID-19 Abroad

Despite being fully vaccinated and generally being in good health, at the beginning of December 2021, I became sick and was diagnosed with COVID-19.

When it comes to public health, I feel and have felt safe in Madrid.

To be honest, I was far more anxious about contracting coronavirus when I was living in the United States as I was working at a people-facing job in a workplace that was visited by hundreds of patrons daily, many of whom did not wear masks without constant encouragement, or simply, at all. I also lived in Florida, which was perhaps a bit infamous for its gubernatorial-level political leadership’s resistance to local and school district mask mandates, as well as the funding, publication of, and access to public research into COVID-related statistics and data.

Conversely, now, I work at a people-facing job here as an auxiliar de conversación, and even, in a school where there are younger children who may not have even been fully vaccinated, I feel generally confident that I am safe. At my school, staff, teachers, and students are all required to wear a mask while on the premises. Teachers are even given our own supply of disposable, medical-grade masks once a month. Additionally, now, a year since the pandemic began, they now have established protocols and resources in place to deal with potential outbreaks or infections. In the larger picture, the autonomous community of Madrid has consistently maintained public health mandates, perhaps due in part to the capital’s status as the global epicentre of the pandemic in the year or so prior, and also, to the effect that the pandemic has had on the European Union at large. It’s definitely a different system to that of the United States. For example, In August on 2021, while I saw mask mandates banned in Florida, in Madrid, public health guidelines were loosened to allow people to not wear masks outdoors (although still required indoors and on public transit), and nightclubs to open at limited capacity, among other things. Four months later, in December, in anticipation of holiday crowds in large public spaces, and with the new emergence of the omicron variant, which was identified in parts of the EU–including Madrid–these mandates were being discussed to be put back in place. Other public health initiatives, like free antigen testing at pharmacies, and availability of booster vaccinations, would also be implemented this month, in addition to heightened travel restrictions. This is all to demonstrate that the local government has been flexible when it comes to its response to coronavirus, and consistent in maintaining basic public health measures.

These observations having been said, it remains that I still contracted COVID abroad.

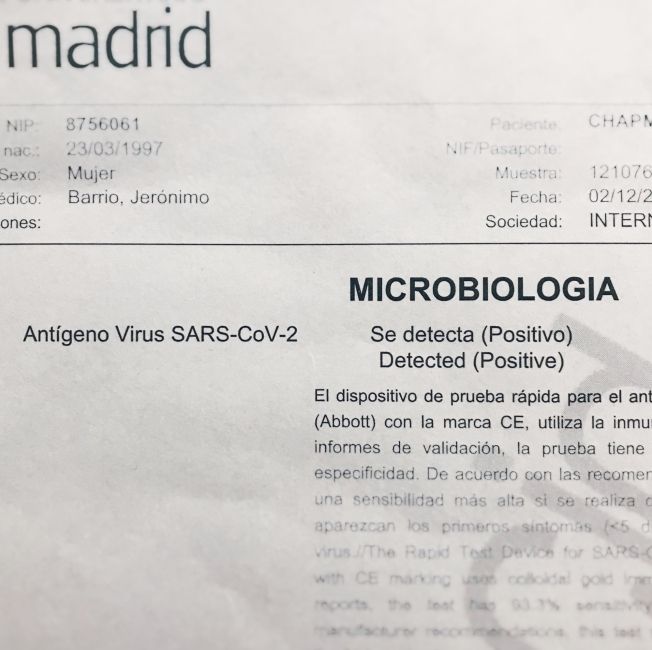

I was diagnosed on Thursday, December 2nd, when I visited the urgent care clinic at HM Hospital Universitario. This is CIEE’s recommended hospital for program participants. It’s at a central location, close to Arguelles, and they have an international department, with docents who are available to help you with paperwork and provide translations and guidance while at the hospital–and with other affairs like billing and contacting insurance. The physician at the clinic told me it was likely an upper respiratory infection, but I requested an antigen test as I was planning on traveling during the puente, or, the long weekend, and needed it anyway. After about an hour of waiting, I received a positive result. I was given a justificante letter for missing work, instructed to isolate for ten days, and to take a general over-the-counter medication as needed.

And so, the ten day isolation began.

I was fairly sick, and although I was vaccinated, I still experienced many symptoms, albeit, I imagine slightly less intense than if I was unvaccinated. I briefly lost my voice the day before, had a minor cough for a day or two, but was severely congested, ran a high fever, and felt really fatigued. I even experienced a brief loss of smell.

Despite my condition, I had a few things to do before I could fully focus on rest. I checked to see if I had enough medication to last the period of quarantine. I sent my justificante to my bilingual coordinator at my school to have work excused. I canceled and rescheduled the trip I had planned, and thwarted any plans for the following weekend. I started on my insurance claim paperwork for iNext (which I have through CIEE) so that I could be reimbursed for my medical expenses abroad. Most importantly, I initiated contact tracing.

For me, contact tracing involved notifying everyone I had been in close contact with over the past few days. Fortunately, I knew I had a concrete window of time to determine who I could have infected–before my antigen test on Thursday, I had also taken one on Sunday and the Friday before (in order to travel), which were both negative. It’s always possible that I could have been infected and yielded a false-negative, especially having taken an antigen test, but since I received two tests with a false result I had confidence that I was not yet infected at that time. Antigen tests determine the presence of active infection, and so, I came to the conclusion that some time in between the weekend and my diagnosis, I may have infected others.

Local guidelines encourage those with whom an infected person has had close contact, or contacto estrecho, including roommates, family members, or people that are in close proximity from day to day, to get tested and also quarantine themselves. My housemates had not been in close contact with me the week prior, and all but one had already left for the puente. I still let them know that I was sick since we shared common areas like our bathroom and kitchen and they would be returning within the timeframe of my quarantine. I let my bilingual coordinator from my school know about my diagnosis, and trusted he would tell the other auxes or faculty I usually worked with. I also got in touch with some private lessons students and parents, as I provide lessons a domicilio, or in house. Most everyone seemed alright, but in the end, my attempt at contact tracing wasn’t futile. One of my friends, who had a few cold symptoms, was diagnosed and told to quarantine the day after I reached out. Although it certainly wasn’t good news, it helped to know that the spread could be mitigated.

With ample sleep, hydration, and medicine, by the third day, I had already broken my fever.

I spent my days working on my assignments from school, making lesson plans for private classes, watching shows and tiktoks, reading, knitting, and scoring high on language learning apps. It wasn’t ideal to be spending so much time in my apartment when it seemed like so many things were going on in the world outside, and despite living or traveling or seeing parts of Madrid vicariously through my friends' instagram stories, I felt a bit despondent. But it wasn’t all bad; friends were nice enough to check in, and drop off groceries, the first couple of nights, my housemate made me pasta and meals to heat up in the microwave while she was gone, and the other auxes at my school sent texts asking how I was feeling.

I had the apartment to myself, so I made sure to air out and disinfect the common areas as much as possible, wearing a mask when outside of my room. It was nice to spend time in a place I usually don’t. It was like a staycation, even if it was mandatory.

As far as work was concerned, I didn’t have much to worry about–I thankfully got sick during a long weekend, so I didn't miss as much as I could have. I had some student writing assignments to proofread to pass the time, and I only missed 4 days of instruction (which is still more than allowed). In the 2021-22 Handbook, the Ministry allows participants in the Auxiliares de Conversación each three days of excused absences. Since quarantine involves at minimum 10 days of respiratory isolation, if an Auxiliar was to be diagnosed with COVID-19 they would miss up to 8 days of instruction–which is of course beyond that allotment. I had to contact my bilingual coordinator at my school and intended to schedule the days I would make up, but was given a pass on account of my doctor’s note for mandatory isolation. This may not be the case for everyone at every school (and certainly, not every auxiliar has the same experience) but it definitely made the anticipation of returning to work much easier.

As quarantine came to a close,

I felt significantly better. Initially, hearing the words that my test had come back positive compounded in magnitude the feeling of doom that had been so ever-present during the pandemic over the past (almost) two years. To think that had I not been vaccinated, had I not insisted on taking an antigen test, had I not reached out to my contacts to see if anyone else was sick, had I simply disobeyed and not isolated, at this point in time, my health and well being, and that of others, could be drastically different. With my fever gone and other symptoms having subsided, I scheduled a test to determine whether or not I had truly recovered.

I may not yet have a general practitioner here in Spain, but there is no lack of testing clinics available in Madrid. After making an appointment online, I visited the Democratest clinic in Azca and received a quick PCR test–I was in and out of the clinic in less than ten minutes on Sunday morning. My results were delivered (in both Spanish and English, which was very cool) to my email inbox the next day, in time to contact my bilingual coordinator about coming back to work. Tomorrow, the 14th, I finally get to see my students again.

Looking ahead, I have to anticipate certain challenges that come with COVID-19 recovery.

In the short term, I know that my immune system is currently battered and will need lots of care to be brought to a standard of health. When I travel, I will not be able to take antigen tests with complete confidence–as, depending on the time since infection and recovery, they can continue to yield seemingly positive results for recovered individuals. Instead, I’ll opt for the more expensive and slightly more time consuming PCR to prove my recovered status. And, if I want to return to the United States, following CDC guidelines, I will have to pursue documentation of recovery from a physician, and eventually register it with the vacunas office so it can be added to my EU digital COVID-19 certificate. Finally, although the pandemic has brought forth insightful research about this particular coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), there hasn’t been much of an opportunity to study the long-term effects of having been infected, or, the likelihood of being infected once again but by a burgeoning mutation. I, and the millions of other people who have contracted and recovered from this virus, have that to look forward to.

Related Posts

The Blog Has A Sister!

It was August 2025 when I started writing this blog - just over 6 months ago, before I left for Spain. To say I'm relieved that I've consistently published my... keep reading

Pack Perfectly Every Time: A Guide to Getting Your Luggage Right

The first time I ever flew alone, I was 14 years old. My best friend had moved to Scottsdale, Arizona, and my mom said that she’d let me fly by... keep reading

10 Travel Tips & Tricks I Live By

Trying to avoid unnecessary stress, enjoy your trip as much as possible, and reap the benefits of spending money? Me too, and it's simple! Below are 10 travel tips I... keep reading