A Summer of Science, Service, and Self-Discovery in Lisbon

The following blog was written by Matt Redman, Vice President of High School Programs at CIEE, who has been with the organization since 2009.

This summer, I had the honor of watching the CIEE Lisbon team in action, as they provide the summer of a young-lifetime for students from all over the United States, as they learn about Marine and Aquatic Science—from rivers, to estuaries, to the ocean—these students get to make the natural environment their classroom and laboratory for three weeks. They will make observations, collect samples, analyze data, work side-by-side with a local NGO to protect the water and to restore dunes all while learning about Portuguese people and culture (and trying new foods, like fish that come to the table whole!).

I was lucky to travel with the students for two days.

Day One: Environmental Action at the Coastline

Beach Clean-Up and Dune Restoration with Brigada do Mar

The first day was beach clean-up and dune restoration day. Students had already been introduced to the NGO Brigado do Mar in a prior activity, which paired them up with local youth—where they had a shared experience to learn and to have fun (sharing dances/versions of dances to similar songs!). The group helped to bring a local perspective to the day that would include four stations: re-securing the dune protection barrier, beach clean-up for plastics, removing invasive plants, and making new signage to help protect the restored area.

Connecting the Dunes to the Local Community

The students’ experience was one that provided them with immediate examples and sensations but with overall context that provided them with historical reference AND future inspiration for work that can be done. The introduction to the Cova do Vapor community provided them with a historical tale of vehicles on the beach, due erosion, loss of sand to the increasing river current, and an historic storm flood in the village. Students learned how degradation of the dunes had occurred and how their degradation was threatening the continued habitability of the village.

Hands-On Learning with Dune Barrier Restoration

When students were introduced to the workstation that was improving the barrier to the restoration area, they were provided with a physical reference for the work that has been completed to date, replanting native grasses to strengthen/rebuild the dunes. The fenceposts that were installed by the CIEE students last year, were now almost completely buried by sand, because the plants capture and hold the sand as dunes. The dune had grown over 2 feet in the past year. Students had to dig the old poles out of the sand to re-position them/the rope they hold, to and effective level to hold out beach-using people—to protect the dunes. Digging out the fence poles provided the students with a visual reference of the plant root systems that hold the dunes in place. The grass roots were exposed, and they could understand that the native grasses are the key to the restoration project as they grow roots up to 35 feet deep! This reference point gave the students a sense that others had done meaningful work before them—the prior restoration and building the barrier; that the work previously performed was achieving the goal of re-building the dunes, as the fenceposts were buried; that they could observe how the dunes were being held in place as they dug out the fencepoles; and they were inspired that the work they were doing was important and would last.

Systemic Thinking Through Environmental Stewardship

The other stations carried similar benefits for developing systems-based thinking, and complete experiential learning cycles:

Plastic Pollution and Microplastics Awareness

The beach clean-up station demonstrated the scope of the plastics problem in the world’s waterways. As the group was encouraged to not only pick up large plastics/waste from the beach but also to use small sieves to remove smaller pieces of plastic—before they become microplastics, they learned that the cycle of plastic waste is one that requires multiple approaches and is complicated—due to the breakdown cycle of plastic waste.

Tackling Invasive Species, One Plant at a Time

The invasive plant removal station provided them to physically help with restoration efforts, while seeing that progress has been made by prior groups with the same mission. The parts of the dunes that had the invasive plants eradicated last year don’t have to be worked on this year! Students see that prior work was meaningful, bringing more meaning to the work they were doing that day.

Sign-Making for Conservation

The sign building station was a nice break from the hot sun, provided some artistic time, where they could bond over the work they had completed. They had fun making something physical that would be left behind to serve the cause of dune protection.

Celebrating Progress and Building Friendships

After the work was over, the students got to enjoy a local lunch at a very local restaurant and then they enjoyed the fruits of their labors with an afternoon of free time on a beach at the mouth of the Tagus river, where they got to be teens “hanging out” – but they were a group of students, from all over the U.S. who had recently formed new bonds and fast friendships. This summer experience was truly special from the learning to the friendships.

Day Two: Scientific Discovery at the University of Lisbon

The second day I traveled with the program was a day spent at the Biologic Department of the University of Lisbon. Again, the students broke up into smaller groups for the activities. Each activity was designed to build skills and perspective in a fun way that the students may not get at home. Additionally, they had exposure to not only the physical presence of a university campus but also got to work with longstanding faculty in the conservation and biology departments; people who have done research and data collection for over 25 years each.

Inside the University Workshops

The activity stations for the students were:

- A role-playing debate about marine research where students had to take the position of different factions: scientists, activists, big pharmaceutical companies, or government.

- A microscope session to scan for and identify different species taken in sediment samples and learn how to think about biologic markers in water quality.

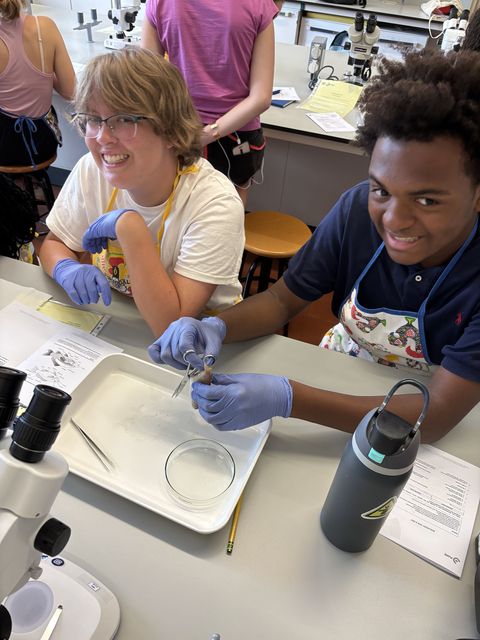

- A fish dissection! (Surprising to me was that only 1 student in the large group had ever dissected anything real before.)

The activities each pushed the students out of their comfort zones in different ways:

In the role play, the students had to think about the motivations and sentiments for multiple audiences, sometimes for positions that they fundamentally disagreed with. The most difficult position for the group I saw was that of Big Pharma—the students were more interested in creating compromise they felt good about, rather than role-playing into a “profit-first” position. The instructor did a great job of pushing them to think bigger in all positions, for example, outlining the consequences of the scientists offering to make their research public as “everyone will have access to your data and could, potentially, use your data to get ahead of your research…”. Students will have lasting thoughts about their roles and the consequences of their positions; real debate is good.

The microscope session provided students with a contrasting option to the chemical analysis of pH quality and water chemistry that they had learned the prior week. The introduction of biologic data as a marker of water quality trades cost of experimentation and equipment with time spent on data collection and analysis. The students had to think about what types of biological organisms may make good markers and why (i.e., what is in place most of the year and all the time? Organisms that live on the or in the Bottom!!!). Then, they got to sift through some sediment samples, using the microscope to identify different species. The highlight was each group got a small crab that they had to explore and find ways to determine the sex of the crab.

The dissection session was a real push for most of the students. The fish samples had to be thawed out from their frozen state (they are caught sometimes months in advance). The smell is not inconspicuous and then cutting into a once living fish was a new experience for all of them! They got to learn about different identifications to determine what species their fish were, using an identification chart (if fish has this type of fin pattern, go to number 4; if fish has eyes on both sides of head, go to number 5, etc.) and then opened fish to extract internals to dissect stomach to try to know what food the fish had consumed before being caught.

Why These Experiences Matter

These two days with the Lisbon program were a joy to witness; I saw students stretching themselves in new ways: thinking critically, working hard, and having a lot of fun along the way. Whether they were digging out fenceposts, dissecting fish, or debating marine ethics from perspectives they didn’t necessarily agree with, they were engaged and learning by doing, connecting ideas across disciplines, and supporting each other as they tried things for the very first time. These experiences weren’t just about science; they were about people, place, culture, and impact. Just as important, they walked away with new friendships, new confidence, and a sense of purpose they’ll carry with them long after summer ends.

Help a student say yes to a summer that matters. Whether you’re a parent or an educator, you can open a door to global learning with CIEE.

Related Posts

Our last days

It is hard to describe what these last few days have felt like for our student. In one sense it feels like we have been here forever— our group is... keep reading

Tomar, Portugal - Portal to the Past

“Everyone put down your things, we have to leave NOW!!!” Chaos. Then the sound of 70 some people- the majority teenagers- running out of a luxury hotel lobby as quickly as possible...